Traffic fears near quarry become reality, neighbors say

There was a time, seven years ago, when Todd Ford could put a hose in the hot tub at his Yacolt Mountain home and fill it with well water. His shallow well, just 15 feet deep, sat atop a natural spring, and the water was pure and plentiful. “Everybody who came up here thought I had the best water,” he said.

No more. “If I were to fill the tub up now, I would get it half full before there was no more water and have to wait for the well to recover,” he said.

The pond in Ford’s yard, where he keeps cutthroat trout and brook trout, has shrunk by half, and like many fish ponds on the mountain, has filled with sediment. “Now you can see a sandbar from our deck,” he said. “The trout are smaller, and there aren’t as many. We had a couple of beaver, but they left.”

Water quantity is not Ford’s only concern.

“Our water is still pretty clear,” he said. “It just became super acidic.” The well water has corroded his copper pipes, causing water to spray everywhere. He ended up replacing mildewed kitchen cupboards and stripping his kitchen floor down to bare wood. At one point, he and his wife moved into the Battle Ground Best Western for a month.

ooo

Shirley Miller has lived in her house near Yacolt Mountain for 35 years. Her well used to produce 35 gallons a minute. She remembers keeping the sprinklers running all day, watering four acres of fields. But four and a half years, ago, when she came home from the hospital after surgery, she noticed a change.

“I’d go in to take a shower and it would quit,” she said. “I would turn it off, soap down, turn it on again.” Now she’s down to one or two showers a week, making do with sponge baths most days. “I had to choose one thing: Take care of the chickens or take a shower,” she said.

Though she keeps a hose in her front yard to water her geraniums, she had to let her horses, goats and vegetable garden go.

ooo

Jim Styers lives on Yacolt Mountain Road right where the road turns and goes up the mountain. He built his house and drilled his well in the early 1970s. The well is in solid rock, protected by 40 feet of casing.

In 2002, when his son hooked up to the well, it was running at top capacity, producing 23 gallons a minute. “In March 2008, we hooked up a bigger pump, and all of a sudden I have no water,” he said. “The water was 60 feet from the top. Now it’s down 200 feet. They say the water table has dropped.”

What these and other families with well water problems have in common is that they live below the Yacolt Mountain Quarry. And some are convinced there’s a connection between the quarry operations and their own failing wells.

So far, they haven’t been able to prove it.

But it’s not as if there weren’t warnings.

ooo

Eight years ago, at the peak of Clark County’s building boom, county commissioners voted 2-1 to permit contractor Brent Rotschy to develop a 100-acre gravel quarry atop Yacolt Mountain. They chose to override hearings examiner Richard Forester, who in November 2002 denied Rotschy a permit to develop the quarry and extract up to 10 million tons of rock. Forester warned that the quarry could cost homeowners the use of their wells.

Rotschy, who owns the mountaintop, leased it to Kelso-based mining company J. L Storedahl & Sons. In September 2008, three years after the quarry got final approval, Storedahl began blasting the top off Yacolt Mountain.

Complaints from residents of the rural neighborhood below the quarry soon followed.

Those complaints would not come as a surprise to Forester, who retired as a Clark County hearings examiner in 2010. At the time, the mountaintop was zoned for timber production. Rotschy applied for a zone change — a surface mining overlay — and a conditional use permit allowing the operator to run a crusher and extract the rock and gravel at a peak rate of 410 trucks per day.

With gravel deposits in rivers increasingly off-limits because of impacts to threatened salmon, Rotschy argued that mountaintop mining was the only alternative available to provide rock for roads and sidewalks in fast-growing Clark County.

The Yacolt Mountain Neighborhood Association posted signs saying ”No Yacolt Mountain Quarry.” Neighbors hired a lawyer and packed two hearings to protest the project. They said the heavy trucks would pose a safety hazard on the narrow, twisting roads in the area. They worried about noise and vibrations from the blasting.

Most of all, they feared what would happen to their wells.

After reviewing detailed hydrological and geological studies, Forester concluded that a large rock quarry would conflict with the quality of life of families that had built houses in the quiet rural area.

“People make investment and lifestyle choices that do not anticipate the disruption that comes from having a mine as a neighbor,” he wrote.

He was especially concerned about how blasting would affect wells in the area.

“No one can predict the impact of the mining on the aquifer and the well water supply until they begin the mining operations,” he wrote. “The applicant is asking the examiner to play Russian roulette with groundwater supply.”

Forester noted that reports showed some wells on the mountain already were running dry. He said the applicants sought to force “innocent bystanders” to bear the risk of damages that could not be predicted in advance.

“The potential risk of depriving adjacent uses of water and therefore effective use of their homes is too great an impact to speculate on,’” he wrote. “The only certainty will come from actual mining and monitoring.”

ooo

Rotschy appealed the denial, and in 2003, Clark County Commissioners Craig Pridemore and Betty Sue Morris voted to overrule Forester and allow the quarry to proceed. They rejected Forester’s argument that the project could not be approved without proof that it would not interrupt the groundwater supply. The county had zoned the Yacolt Mountain area for resource production, not rural living, they argued. Commissioner Judie Stanton was the lone dissenter.

County attorney Rich Lowry told the commissioners they had little latitude to deny the proposal unless they could point to problems identified in an environmental impact statement. But the county had not required Rotschy and Storedahl to prepare an EIS for the project, and opponents of the quarry had failed to file a timely appeal of the decision not to require one.

Forester set 117 conditions of approval for the applicant to meet if the project went ahead. The county whittled that list to 10. One says the quarry operator “shall modify or replace groundwater wells that are shown to be adversely affected by the proposed surface mining activity.”

That condition hinges on the words “shown to be.”

As Forester warned, proving a cause-and-effect relationship between mining and falling groundwater levels is not a simple matter.

Some nearby homeowners are convinced Storedahl is illegally pumping water from the aquifer beneath the mountain, thereby depleting their wells. It’s an assertion that company president Kimball Storedahl denies.

Storedahl is allowed to withdraw up to 5,000 gallons of stormwater runoff daily without getting a state water right. That water is stored in two detention ponds at the quarry. “We use it when the crushers are operating,” Storedahl said.

The company also has a monitoring well. “It tells us where the groundwater isn’t,” Storedahl said. “When we drilled the well, we drilled down 250 feet and drilled a dry hole. There was no water.” The well has since partially filled with stormwater, he said, but no water is pumped from it.

Ron Wierenga, manager of clean water programs for Clark County, says he takes the company at its word. “To our knowledge, they are using only groundwater,” he said. “If they were using more than 5,000 gallons, they would need a state water right.”

Monitoring conducted on the mountain between late 2006 and late 2007 established a baseline for groundwater levels in the area. The monitoring plan for the project called for an assessment and a report after “significant quarry activity,” defined as at least 10 acres of disturbance.

David Rogers and Howard Jones say they began experiencing changes in their wells even before quarry operations began, during construction of an access road on the mountain.

“This whole mountain is fractured rock,” said Jones, who lives along Kelly Road west of the mountain. “When you blast, everything goes straight down. They’ve just completely ruined the aquifer.”

Jones lost his well water entirely in 2006, and had to hook up to public water.

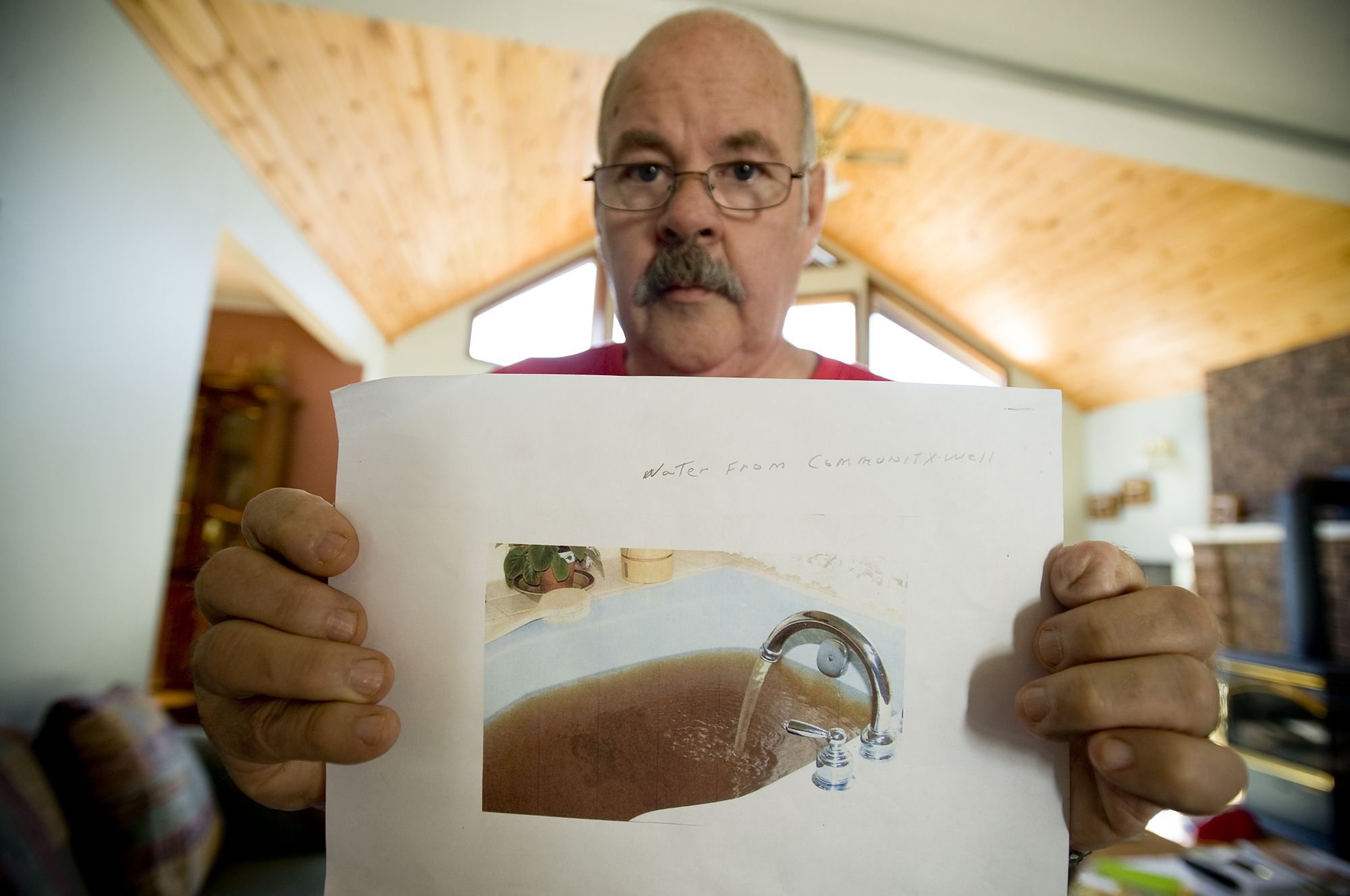

Rogers, a blunt, often abrasive retired Machinists Union negotiator, built his house near Yacolt Mountain in the late 1970s. He had a 610-foot-deep community well drilled in 1978 to serve five houses, including his own.

Gradually, after 2001, Rogers’ well silted up. He too was forced to hook up to the Hockinson water system, served by Clark Public Utilities, at a cost of $12,000, to get potable water to his house. These days, he uses his well mainly to water his vegetable garden and fill his fish pond, which has steadily filled with sediment.

Both men blame the mine, and point to Forester’s warning nine years ago. “Why should we even have to sue the county to correct this problem when the county was told in 2002 exactly what would happen?” Jones asks.

Kimball Storedahl says there’s no evidence that the quarry is to blame.

“The groundwater people who have looked at this and have done the analysis have found no reason to believe that any of the operations up there have affected any private wells in any way, shape or form,” he said.

ooo

This spring, when neighbors began showing up at county commission meetings to demand action on well water and traffic safety concerns, commissioners hired Axel Swanson, a former Cowlitz County commissioner, to listen to their complaints, gather information from county and state agencies, and try to get to the bottom of the problems on Yacolt Mountain.

Swanson asked Wierenga to review the quarry operators’ monitoring reports on groundwater and well water. “I wouldn’t say every i was dotted, every t crossed,” Wierenga said. “We should have been getting regular reports throughout the operational period.”

Under its conditional use permit, Storedahl was required to test wells, inspect house foundations and alert homeowners closest to the quarry in advance when blasting was to begin.

Todd Ford said he asked for all of those things when Storedahl called him in 2006. “I said yes, but they never did any of those things,” he said. “And this is one of the houses where they were supposed to monitor (well water) monthly.”

Storedahl said the company complied with the requests it received. “Typically, they were one-time inspections, just to document any foundation cracks, cracks in walls, any flaws prior to blasting.”

This spring, the county directed Rotschy and Storedahl to commission a study to find out whether there was a pattern of fluctuating groundwater levels on the mountain after blasting began.

The operators’ consultants, Maul, Foster and Alongi, set out to monitor 15 wells and one spring on the mountain, but due to access problems and other obstacles, they were only able to compile complete reports on seven or eight wells, Wierenga said.

The consultants’ May 9 report concluded that “water level measurements remained static throughout the monitoring period and did not show any significant variations.”

“While individual well water levels did vary between months, there were no wells in which the groundwater elevations consistently decreased or increased,” the report noted.

An independent study commissioned by the county drew a similar conclusion.

Swanson told commissioners in a May 25 memo that, despite some areas of concern, “generally, the quarry is operating in compliance with the conditions of final site plan approval and the conditional use permit.”

ooo

Clark County Commission Chairman Tom Mielke, whose district includes Yacolt Mountain, concedes that the county took an out-of-sight, out-of-mind approach to the quarry until recently. “The more we looked into it, the more we found a lot of things had been skimmed over,” he said. “Nothing was ever followed through on,” he said, like a requirement that the companies reach out to the neighborhood and form an advisory group on quarry issues.

But on the key issue of the mine’s impacts on domestic wells, the new studies appear to hold the quarry operators not liable.

“We can’t positively say today that that mine had anything to do with those wells going dry,” Mielke said.

“I firmly, absolutely believe the quarry has not affected any of their wells,” Brent Rotschy said. “I think there’s a logical, reasonable explanation for every one of them. “

Jim Styers has no doubt there’s a connection between the blasting and what has happened to his well. “They would blast at night,” he said. “The next morning, there was no water in my well. What happens is, the pump runs dry. When I do a load of clothes, I’d better do one load, not two or three.”

During a 30-year career in construction, Styers said he learned a thing or two about explosives. “When you blast, the powder is going to take the path of least resistance. If my water is coming from a crack in the rock,” blasting is bound to affect it, he said.

The question, he said, is, “What are they going to do to make it right? They might suggest we hook up to city water. But I have good, clean water. When I go down to Battle Ground, I can’t drink the water there.”

“If there’s a chance the quarry was involved, I’d do what I could to help them out,” Brent Rotschy said. “The problem is, as soon as you do it for one neighbor, you have to do it for everyone.”

Mielke said he met with Kimball Storedahl and asked whether, “in the interest of being a good neighbor,” the company might help pay the cost to bring water to neighbors who have lost their wells.

“As far as being a good neighbor, I think I would just have to reserve my answer,” Storedahl said. “If we can find any reason that we may have had a negative effect on people’s well, we would consider some type of assistance.”

Some of the wells that have failed “were not good wells when they were drilled,” he said. “They were minimal at best.”

Clark County itself can’t reimburse people who have lost the use of their wells, Mielke said. “We cannot for sure identify the cause, and until we can do that, we don’t want to take on that liability.” Already, the county has spent “enormous resources” trying to resolve the issue, he said.

However, commissioners have agreed to take advantage of state money that might shed light on the condition of the aquifer. On Tuesday, they voted unanimously to apply for two state health department grants of $30,000 each. One would fund a six-month study of water quantity and availability issues in the north end of the county west of Yacolt. The other would fund a 12-month study of nitrates in the groundwater near Yacolt.

Rogers wants to hire a lawyer and shut the Yacolt Mountain Quarry down. He has contacted state and federal officials about the silt that is washing into streams and ponds on the mountain. He’s convinced the quarry is responsible.

But Jones says a legal victory is a long shot.

“I don’t believe there is any way that all of us together are going to be able to shut down the pit,” he said. “They’ve got more money than we do. But at least we should be reimbursed.” His own out-of-pocket costs amount to about $25,000, he said.

Richard Forester, whose warnings were disregarded nine years ago, said it’s not fair to expect Yacolt Mountain residents to dig into their own wallets to hire expert geologists and hydrologists to try to prove a direct link between quarry operations and the deterioration of their wells and ponds.

“The county permitted those people to build those homes,” he said. “The county has to take responsibility if there are other values that are highly important but that may put an unfair burden on residents for a good that the county desires.”

Kathie Durbin: 360-735-4523 or kathie.durbin@columbian.com.